Leadership used to be messy, thoughtful, human work. Now, it risks becoming a lifestyle product—complete with listicles, morning routines, and pastel-quote inspiration. That is the essence of Satish Pradhan’s post titled “The Seductive Simplicity of ‘7 Steps to Greatness’“. Satish is a thought leader I immensely respect and whose views have guided me for a while now. This time, as always, his writing offers a sharp take.

He writes: “Leadership becomes a lifestyle—a performative state of constant optimisation and vague inspiration.” Ouch. True.

I couldn’t help but add this in the comments:

“Also begs the question—who made it this way?

Boards, wanting bandaids?

Leaders, craving a formula?

HR, trying to package potential?

Consultants, with frameworks that look good on slides?

Academia, chasing citations over messy reality?

Or TED Talks, with applause timed to the speaker’s smile?

Not a blame game. Just a call to reflect.

If leadership is now theatre—who wrote the script?

And more importantly… who’s still reading the footnotes? 🙂”

Truth is, we didn’t land here overnight. As I wrote earlier in a piece titled “Decline Creep,” these shifts happen gradually, then suddenly. The seductive simplicity of seven steps isn’t a glitch—it’s a feature of a broader cultural operating system.

Leadership development is a multi-billion dollar global industry. Estimates put it at over USD 350 billion annually. With that kind of investment, you’d expect profound change. We often get ‘pass me the popcorn’ stuff.

The Current Cultural Operating System

The milieu we operate in shapes our defaults. Leadership and its development has not escaped the broader shift toward speed, scale, and surface over substance. Here are some attributes of this time and space.

1. Everything must be tangible.

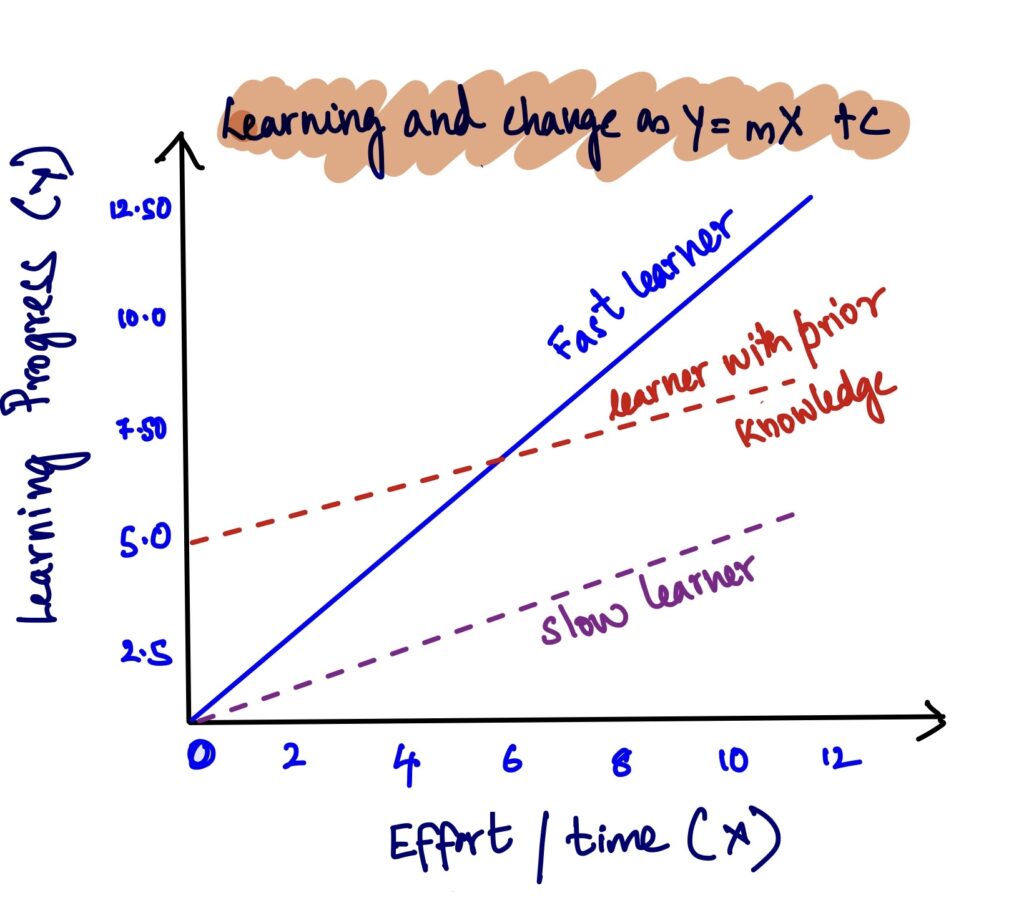

If it’s not tangible, it must not matter. This is a tragic oversimplification. Real progress in leadership is often subtle. A better conversation. A delayed reaction. An unexpected apology. Tangible, if you know where to look—and if you look with intent.

Deep learning and behavioural change are not immediately visible, but they are transformational over time. Sitting with the intangible, the ambiguous, the unresolved—this takes patience. But that’s precisely what we seem to be losing.

2. We live in a fast-food world.

Everyone wants nourishment in the form of a nutrient bar they can eat before catching a train. Sure, it feeds the immediate hunger. But it cannot offer the satisfaction of a full-course meal. Or the long-term health. Leadership frameworks are now nutrition bars: portable, efficient, and forgettable.

Herbert Simon, who coined the term “bounded rationality,” reminded us that humans tend to satisfice—settling for what’s good enough. Quick lists cater to that tendency. But leadership needs more than adequacy. Over time, ‘adequate’ becomes the benchmark. And then the ceiling.

3. The tyranny of the quarterly result.

The short term is now. The long term is the next quarter. It’s as if the world will cease to exist beyond the quarter. If something doesn’t shift short-term metrics, it’s dismissed. Leadership development doesn’t always give you a spike in numbers. Sometimes it just quietly prevents a disaster. Or helps someone stay.

Peter Drucker is often quoted as saying, “What gets measured gets managed.” Full stop. But that’s not where he stopped. He actually said: “What gets measured gets managed — even when it’s pointless to measure and manage it, and even if it harms the purpose of the organisation to do so.”

Perhaps we were in a hurry and didn’t soak up the full sentence.

4. The obsession with machine-like efficiency.

We’ve come to admire speed, standardisation, and output so much that we expect people to behave like machines. Fast. Predictable. Always on. That logic has quietly crept into leadership development too.

It’s now packaged like a factory model—designed to scale, deliver uniform results, and run on schedule. But leadership doesn’t work on conveyor belts. It doesn’t follow a clean workflow or offer batch processing.

People are messy. They take time. Conversation. Reversals. Detours. Leadership requires recalibration, not just repetition. Efficiency looks good on paper. But it rarely builds trust or courage.

This obsession leads to box-ticking: feedback session done, 360 report filed, coaching logged. But that’s not growth. That’s admin. Cookie cutters work well with cookies—not people.

5. We’ve unhooked from research.

There is a deep and evolving body of work in the social sciences and leadership literature—decades of inquiry into motivation, learning, group dynamics, and organisational culture. Thinkers like Chris Argyris, Edgar Schein, and Mary Parker Follett have explored the nuances of influence, systems thinking, and human potential. Their work offers complex, often uncomfortable truths.

But such research rarely makes it to the glossy handouts or keynote slides. Why? It demands thought. It questions assumptions while resisting slogans. And isn’t easily reduced to three boxes and a circle.

Instead, we pick up ideas stripped of their richness—psychological safety as a checklist item, or systems thinking reduced to bullet points. The substance is lost in the translation.

Academia speaks in nuance. Practitioners crave action. Somewhere in between, we abandoned the bridge.

We need to reclaim it. Not for the sake of theory—but for depth, integrity, and honest conversation. Leadership deserves nothing less.

6. Deliberate effort on development is seen as optional.

Focused development is treated like a side hobby—something to do if there’s time. A luxury. Not core. There’s a comforting belief that leadership emerges on its own. That wisdom arrives with age. That real work is separate from leadership work.

But the demands are more complex now. The path to leadership is often shorter, with less grounding. And the illusion of expertise is everywhere. Ten-second clips pass off as wisdom. Everyone has an answer. Few ask better questions.

What’s missing? Time. And deliberate effort. To learn. To experiment. And reflect. The pause to ask, “What did I learn from that?” feels indulgent. But without it, growth is shallow.

7. Real change happens at work. And it is bespoke.

You can have perspective in a classroom. Maybe even a breakthrough in an offsite. But change? That happens on the ground. In Monday meetings. In the pause before a reply. When noticing what you once missed.

One size doesn’t fit all. It doesn’t even fit most. What works for one leader may confuse another. The best leadership development is bespoke—stitched with care and context. You can learn from shared perspectives. But applying them? That’s personal. That cannot be outsourced.

As Manfred Kets de Vries once quipped, “Leadership is like swimming—it cannot be done by reading a book about it.”

Change is contextual. It escapes formula. It demands participation. So yes, the seven steps might sell. They might even help a little. But let’s not forget: leadership is a practice. Not a product. Not a performance. And definitely not a PowerPoint.

It is messy, slow, human work. And if we want real change, we must learn to value that again—even when it doesn’t come with a checklist or a bestselling cover.

So, there. 7 points. Stacked and ordered. I have a few more. But they won’t fit seven. I am part of the problem you see 🙂

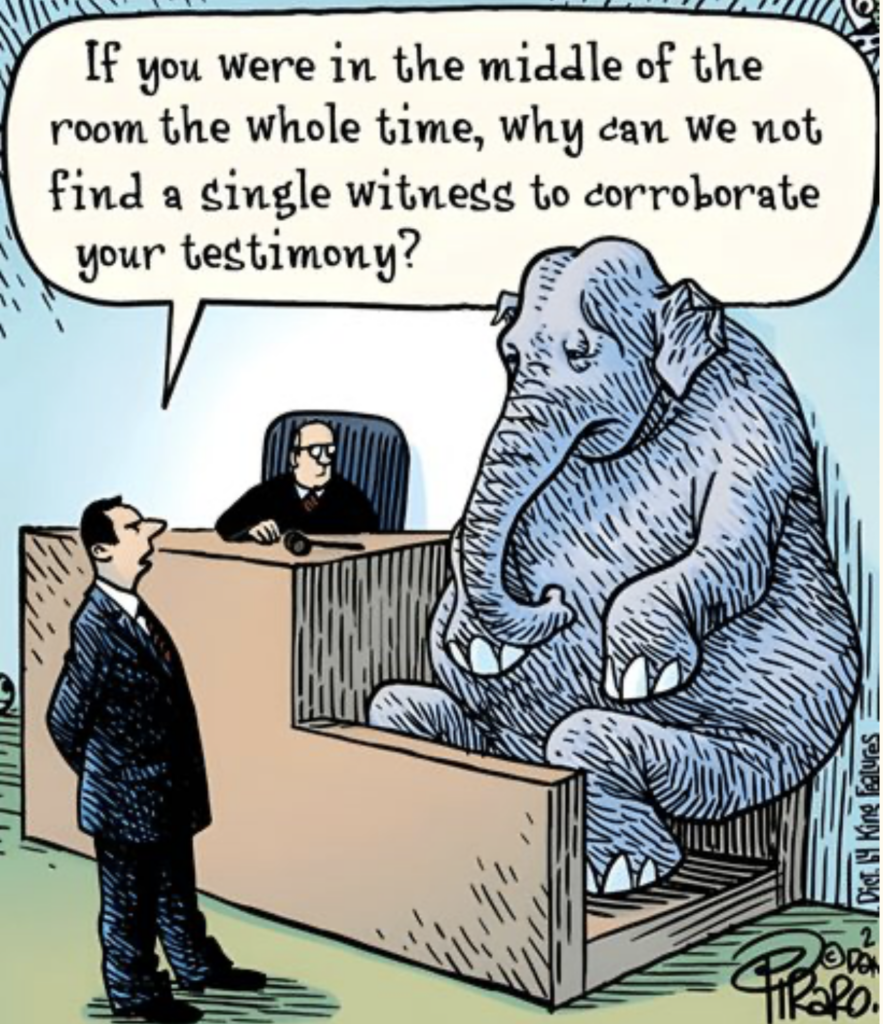

I Am the Traffic

A road safety campaign in Sweden once carried a brilliant line: “You are not in traffic. You are traffic.” Simple. Sharp. It flipped the narrative—from blame to ownership.

That idea travels well. In leadership, culture, and checklist thinking, we aren’t bystanders. We’re not stuck in the system. We are the system. Participants. Sometimes even enablers.

It was never just about traffic. It was about agency. And responsibility. In many ways, it’s a reminder for all of us engaged in leadership and development work.

We may not like the system. But let’s admit it—we help make it. Through what we reward. What we tolerate. And what we scroll past without question.

Culture is not created in boardrooms alone. It’s created in choices. Daily ones. A ticked box here. A skipped conversation there. Over time, these become norms.

We are not stuck in it. We are it.

Development doesn’t happen by accident. It needs intentional choices. Time. Attention. Depth.

So, what do we do? I don’t know. Perhaps, start with Satish’s post. Maybe read the comments. Linger. See what resonates. What provokes. What’s missing.

Because no framework—however snappy—can replace the quiet courage of doing the hard, human work of change. And yes, let’s still read the footnotes. 🙂