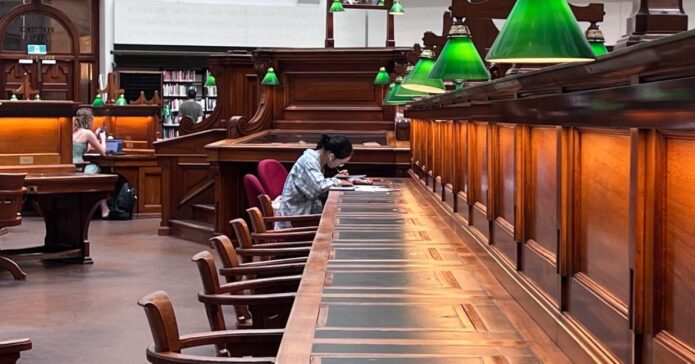

As you enter Mumbai’s Terminal 2’s domestic departure area after the security check, and head towards gates 40-45, there was a favourite bookstore of mine.

Yes. Was.

Because it closed recently. I am usually early for my flights. Sometimes just to get to some books and power my reading. At other times, to see what book catches people’s attention!

I have a sense of loss. I don’t know what will replace it. The frenzy with which eateries pop up everywhere, probably one more eating joint. Maybe a clothing store. Or bags. Always bags. (Sigh).

It makes me think of reading itself. And what we miss.

The Shrinking Discipline of Reading

We’re not just losing the habit of reading books.

We’re losing the discipline of reading anything that asks for more than a glance.

As Stowe Boyd writes, “For millennia, people have offloaded aspects of cognition — such as memory — to written materials. But people still had to do the initial cognitive work of understanding and transposition. And, on the other side, people had to read and comprehend what was written by others, to gain a reflection of the understanding of the author.”

From Written Thought to AI Summaries

Today, that chain is breaking. Reports became memos. Memos became emails. Emails became Slack messages. And now, “people are using AI to read and write even these fragmentary comments.”

Boyd quotes Tom White: “Most books should be articles, most articles should be paragraphs, most paragraphs should be sentences, and most sentences should be silence.”

Here’s the kicker: people won’t read emails beyond eight lines — even from their bosses. God help bosses, did I hear you say? They’re fine. AI is summarising for them.

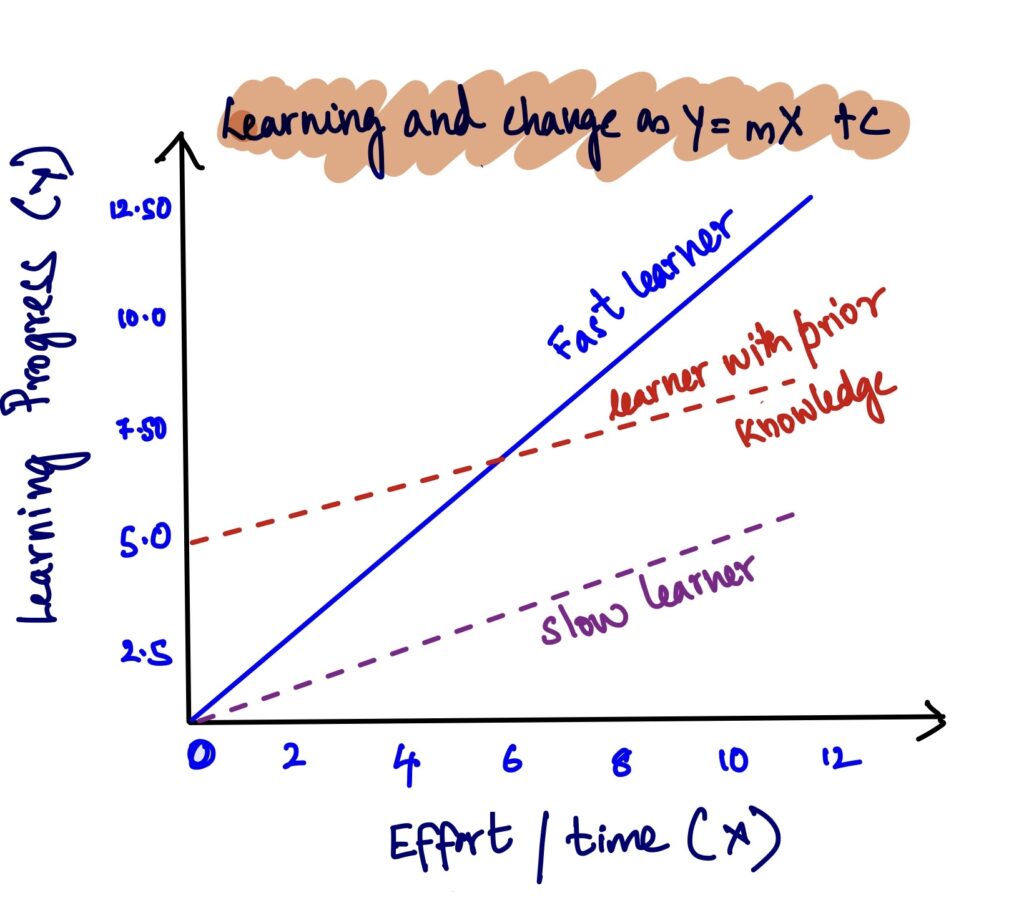

The problem is assimilation. And, reading is more than just receiving words; it’s processing them. Making connections in your own head. If AI does all the summarising, it’s like outsourcing your gym workout — convenient, but you lose the muscle.

The Unfair Fight for Attention

And let’s be honest — this isn’t going to reverse. The future will bring more screens, shorter bursts of content, and ever‑smarter AI eager to do your reading for you. The reading muscle will only get less exercise.

Kids today grow up in a tilted contest: screens arrive first, books much later. By the time reading is formally taught, the screen has already claimed prime territory in their attention span. Erik Hoel calls this literacy lag.

Which is why the habit of reading has to be seeded early and guarded fiercely. If the tide keeps pulling us toward shallower, faster content, the ability to read deeply will become one of the rarest — and most quietly powerful — skills you can have.

Which brings me to Schopenhauer. Who said, “A precondition for reading good books is not reading bad ones: for life is short.”

These days, the search for what to read is as important as reading itself. For there are more recommendations than reasons. Bestseller badges. Must‑read lists. Reviews that can be bought. And so on.

So, how do you find good stuff to read? Thats the challenge. Only, It doesn’t stop with that.

The Collapse of Common Sense

The other day, I was reading a newsletter by Lauren Razavi. She writes about Frank Furedi’s call to revive ‘common sense’.

Furedi says common sense used to come from slow rhythms and shared streets. We moved through the same places. Worked on the same schedules. Spoke the same language. Words meant the same thing to everyone.

These days, the feed never stops.

The same event can be a conspiracy, a tragedy, or a non‑event — depending on who your algorithm thinks you are. Truth bends to the angle of your timeline. And if truth bends, so does taste. The book that trends in your feed may never appear in mine.

We no longer inherit a set of books, ideas, and references by simply living in the same world. The shared shelf has collapsed. The common understanding has evaporated right under our fingers.

Furedi’s warning is that when those shared cultural anchors disappear, what we once took for granted as common sense no longer comes ready‑made. We have to construct it ourselves — piece by piece.

And that changes reading entirely.

Why Reading Well Matters More Than Ever

When there’s no “everyone” anymore, your sense of what’s worth reading can’t just follow the crowd — because the crowd you see isn’t the same crowd I see.

That makes reading well, harder. It also makes it more important. The choice of books becomes less about taste and more about survival — a way to anchor yourself when the cultural map falls apart.

There’s a Jain proverb: When the student is ready, the master will appear. I think books work the same way.

When I’m ready, the book will appear. In a conversation. In an email. Leap out of a newsletter. Or yes, even from an algorithm that gets it right by accident.

The real work, then, is not just to find books. But to ready myself so the right books can find me.

Reading Beyond Reading

Most people read to get to the last page. I read to explore what the book does to me along the way. Because reading isn’t just about finishing. It’s about what sticks. What shifts. What makes you look at something differently the next morning.

So, here is a manifesto Manifesto for Reading Beyond Reading — for letting the book live on in how you think, speak, and act.

A Manifesto for Reading Beyond Reading

1. Read and reread.

Each book speaks to you differently at different points in your life. Your context shifts. The lines may be the same, but the meaning changes. The book hasn’t changed — you have. I first chanced upon Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance in my father’s stash of books. Something he tossed at me with a smile. As a high‑schooler, I read the words. Much later in life, it changed my worldview completely.

2. Choose your curators, choose your context.

Curators are sharing their perspective. It’s up to you to make sense of it in yours. If you know a curator’s taste, you won’t be sold — you’ll be choosing. There are the experts and bibliophiles like Shiv Shivakumar, Mal Warwick. There are friends like Manu and Krishna who bring such fabulous richness. And then newsletters, like Founding Fuel‘s, that have been life‑changing in pointing me to books that have altered mental models of life and living.

3. Don’t read in straight lines.

Don’t stick to one subject, style, or form. Travel writing gives you more than geography. Biographies give you timelines woven into events. Business writing offers you frameworks for thinking about work. Fiction often gives you reality checks. Read history, science, memoir, essays, and newsletters. Step into other people’s heads and see how they think — that’s more valuable than any tidy summary of their thoughts wrapped between covers.

4. Slow down.

Buying. Reading. This can be your one rebellion against speed. Some read to finish. I read to open my mind. Joy comes not from “The End” but from the journey and the connections it sparks.

5. Make reading your calling card.

Slip it into your hello: “I’m in the middle of…”. Ask others:

- What are you reading now?

- Which book surprised you most?

- Which book do you keep giving away?

- If you could reread one for the first time, which would it be?

6. Work your reading.

Scribble in the margins. Fold pages. Argue with the author. Tell a friend about it. Link it to your work. Gift it to someone who’ll love it. A book isn’t finished when you close it — it’s finished when you’ve done something with it. In fact, it’s never truly finished.

7. Let the right books find you.

Stay ready. Be curious. The most important books often appear when you’re ready for them, not when you schedule them.

That’s where I stand. For now.

Tomorrow I may find a new book, and it will smuggle in a new rule.

Until then — what would you weave into this manifesto?