AI is breaking boundaries and dismantling old ways of thinking. It has made a rather impolite but firm introduction to irrelevance. Leaders today must prioritise unlearning for success in an AI-Driven world —or risk being left behind.

AI is rewriting the rules of work, creativity, and competition. Every day, new breakthroughs make yesterday’s expertise obsolete. The old playbooks? No longer enough. The rate of change is massive. And it’s not slowing down.

The real question is: How fast can you adapt?

I clicked the picture above somewhere in Ladakh, where our car had been halted by an avalanche. Workers were labouring to clear the road, knowing full well that another could strike at any moment. That’s the nature of avalanches—sudden, disruptive, and unforgiving.

AI is that avalanche. In the real world, avalanches block roads. In the metaphorical world of fast change, they bury careers, industries, and entire ways of working. The only way to survive? Move, adapt, and find your slope.

Slope and Intercept

A professor whose work I follow is Mohanbir Sawhney. He wrote a piece titled “SLOPE, NOT INTERCEPT: WHY LEARNING BEATS EXPERIENCE” in LinkedIn. The piece resonated and helped me refresh my high school coordinate geometry 🙂

I have been thinking about it ever since. So, Indulge me for the next couple of minutes. Here we go.

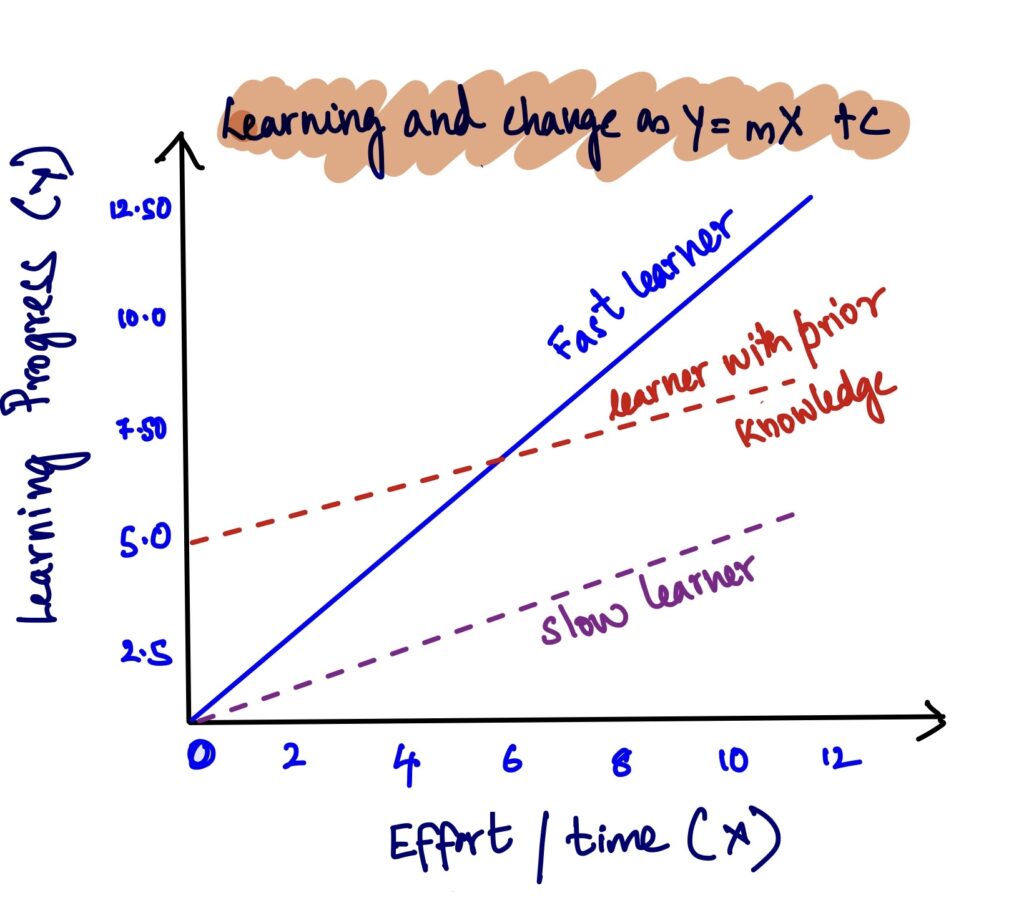

Equation of a straight line: y = mx + c

m: The slope—indicating how fast you’re learning.

c: The intercept—representing your starting point or existing knowledge.

Imagine three learners. Mr. Red starts ahead (high intercept) but learns slowly (low slope, small ‘m’). Mr. Purple starts lower (low intercept) and progresses steadily (moderate slope, medium ‘m’).

Ms. Blue starts behind (low intercept) but picks up new skills quickly (steep slope, large ‘m’), eventually overtaking both. Over time, Ms. Blue’s higher slope (greater ‘m’) allows her to progress faster, proving that the speed of learning (slope) matters more than where one begins (intercept).

That’s Prof. Sawhney’s point. In a world moving at breakneck speed, slope beats intercept every time.

It’s a neat explanation that accentuates the importance of learning and the role of past experience. Which is the point to this post. Past experience can interfere with future learning.

What gets in the way of learning and change? Three things stand out for me.

1. Past Success is a Sneaky Obstacle

What got you here won’t get you there. Yet, we cling to past knowledge like a badge of honour. The problem? Yesterday’s wins can become today’s blind spots.

The best learners stay humble. They don’t assume what worked before will work again. Instead, they ask, “What do I need to unlearn to make space for what’s next?”

This isn’t just opinion—it’s backed by another favourite professor, Clay Christensen, in his classic work, The Innovator’s Dilemma.

Christensen showed how successful companies often fail when disruption hits. Why? Because their past success locks them into old ways of thinking. They keep optimising what worked before instead of adapting to what’s coming next. That’s how giants lose to scrappy newcomers unburdened by legacy thinking.

Exhibit A: BlackBerry

Once a leader in mobile technology, BlackBerry clung to its physical keyboard design, convinced loyal customers would never give it up. Meanwhile, Apple and Samsung bet on full-touchscreen smartphones. BlackBerry’s refusal to move beyond its own past success led to its decline.

Exhibit B: Zomato

Contrast that with Zomato. It started as a restaurant discovery platform but saw the market shifting. It let go of its original success model and pivoted to food delivery. Then to restaurant supplies. Then to quick commerce. By unlearning what had worked before, Zomato stayed ahead.

The same applies to individuals. If you define yourself by what has worked before, you risk missing what could work next. Adaptation isn’t about forgetting your strengths; it’s about not letting them become limitations.

2. Fear Kills Growth

New learning requires trying. Trying involves failing. And failure—especially when experience has given you relevance—can feel uncomfortable.

Many don’t fear learning itself; they fear looking foolish while learning. That’s why kids learn faster than adults. They don’t care if they fall; they just get up. Adults, on the other hand, hesitate. They protect their image, avoid risks, and stick to what keeps them looking competent.

This isn’t just instinct—it’s backed by research. In The Fear of Failure Effect (Clifford, 1984), researchers found that people with a high fear of failure avoid learning opportunities—not because they can’t learn, but because they don’t want to risk looking bad.

Think of it this way: If you’re only playing to avoid losing, you’re never really playing to win. The antidote? Make experimentation a habit. Small experiments create room for both success and failure—without the fear of high stakes. They provide just enough space to try, adapt, and grow.

Reflections on Rahul Dravid

Rahul Dravid’s career is an interesting study in adaptation. Once labelled a Test specialist, he gradually refined his game for ODIs, taking up wicketkeeping to stay relevant. Later, he experimented with T20 cricket and, post-retirement, started small in coaching—mentoring India A and U-19 teams before stepping into the senior coaching role. His evolution wasn’t overnight; it was a series of calculated experiments.

3. New Minds, New Paths

Left to ourselves, we reinforce what we already know, surrounding ourselves with the same familiar circles—colleagues, family, and close friends. That’s exactly why new perspectives matter. We don’t have enough of them. Our past experiences shape our networks, and over time, we rely on the same set of strong connections, limiting exposure to fresh ideas.

Sociologist Mark Granovetter’s research on The Strength of Weak Ties (1973) found that casual acquaintances (weak ties) expose us to new ideas and opportunities far more than close friends or colleagues (strong ties). Why? Because strong ties often operate in an echo chamber, reinforcing what we already believe. Weak ties, on the other hand, bring in fresh perspectives, unexpected insights, and access to new fields.

A few years ago, an MD I know took up cycling. What started as a fitness and lifstyle activity became something more. As he grew more integrated with his diverse cycling community, I saw firsthand how it influenced him—not just physically, but mentally. He hasn’t just learned new skills; he has unlearned old assumptions. His outlook, I realised, has changed simply by being around people who think and live differently.

He has transformed without realising it and is thriving professionally. I’ve been working on the sidelines with him and can see the transformation firsthand. I am not undermining his professional challenges and success, but I cannot help but see the changes his cycling community has brought to him.

The world is moving fast. The only way to keep up? Have more unexpected conversations, seek out people who challenge your views, and surround yourself with thinkers from different worlds.

Sometimes, seeing others take risks in adjacent spaces is all the permission we need to start experimenting ourselves.

Opportunity for Change

The ability to learn, unlearn, and adapt has never been more critical. In a world shaped by AI, rapid disruption, and shifting industries, clinging to past successes is the surest way to fall behind. The real competitive edge lies not in what you know today, but in how quickly you can evolve for tomorrow. Unlearning for success in an AI-driven world is mandatory.

So, ask yourself: What am I absolutely sure about? Because that’s often where the biggest opportunity for growth lies.

The world belongs to those who can learn fast, forget fast, and adapt even faster.